(Here is the Georgian version / ქართულად)

(Here is the Russian version / НА РУССКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ)

by Alexander Kaffka

The officers of Stalin’s secret police actually counted the amount of Usakhelouri wine produced, and made sure the peasants did not retain a drop of precious product for personal use. It’s small wonder that almost nobody knew about this rare wine, and even fewer had ever tasted it.

Above all the fuss

29.10.2015. While visiting a supermarket in Tbilisi, a business traveler or a tourist can rarely miss the wine department. Usually, it is the liveliest spot of every shopping center, with some action taking place all the time. Surrounded by other departments’ lonely and ordinary-looking shelves, the wine place is the one, which is inhabited - by promoters. They are usually charming girls in colorful national costumes, who welcome you and offer free wine tasting. Yes, they are promoting their products but they are acting in such a delicate and friendly way, that you feel they just want to make your life better. The lucky traveler is offered a pretty amazing choice of wines to try, which are generously poured into full-size glasses (not microscopic plastic thimbles used for promotions elsewhere in the world). Easily and without any pressure, after one or two sips, you realize you are in a country where wine indeed plays a very special role.

After several visits paid to such wine departments, a typical foreigner may become perfectly aware of various brands of Kindzmarauli, Rkatsiteli, Mtsvane and dozens of other hard-to-pronounce but delicious Georgian wines – without spending a dime. But there is one wine, which is never offered for free, and for a good reason. It’s the Usakhelouri (here is how to pronounce: Oosa-hello-oory), dark red semisweet wine made of one of the most rare of Georgia’s whopping 400 grape varieties. Usakhelouri wines are expensive, hard-to-find in Georgia and almost completely unavailable abroad. Because of its rarity and high price, this wine is little known even among Georgians themselves. Usually bottled in elegant, slender non-standard glassware, Usakhelauri stands in solemn solitude on a remote shelf of the wine department, far above all the fuss of daily promotions, fenced by its price tag from the casual shopper, waiting for the right connoisseur.

I find it rather pointless to describe the taste of wine in writing. If you are lucky to be reading this in Georgia, you may invest in a bottle of Usakhelouri and taste it yourself in a company of friends (Yes, the price is rather high for a Georgian wine but still is comparable to the cost of a good dinner in a restaurant, so it is not unaffordable.) If you are outside of the country, but still are familiar of Georgian wines, just remember the best Khvanchkara you have tried - not too sweet one – and imagine something much more fresh, rich and elegant. If you like this idea, maybe you’ve just got another serious reason for paying a visit to Georgia.

The wine as a matter of national security

Why is Usakhelouri so little known? There are several reasons for that. Historically, most of the Georgian wine brands were primarily consumed by the vast markets of former USSR; the wines were mass-produced and well known to the people. Therefore, the Georgian wine names such as Saperavi or Mukuzani are still recognizable across the former Soviet republics; the sales in those countries do not require additional marketing efforts, and this is why these countries are still the largest importers of Georgian brands. In contrast, the Usakhelouri’s story is different. This wine was never sold to ordinary people. All the wine produced was shipped to Kremlin, to serve the drinking needs of the government and communist party leadership.

Why is Usakhelouri so little known? There are several reasons for that. Historically, most of the Georgian wine brands were primarily consumed by the vast markets of former USSR; the wines were mass-produced and well known to the people. Therefore, the Georgian wine names such as Saperavi or Mukuzani are still recognizable across the former Soviet republics; the sales in those countries do not require additional marketing efforts, and this is why these countries are still the largest importers of Georgian brands. In contrast, the Usakhelouri’s story is different. This wine was never sold to ordinary people. All the wine produced was shipped to Kremlin, to serve the drinking needs of the government and communist party leadership.

When I say “all” I mean that literally 100 percent of the wine produced: Since 1930-40-s, the production of Usakhelouri was strictly guarded by the internal affairs ministry (NKVD), so not a drop of precious drink could be left without government control. Supply of Usakhelouri was indeed considered very seriously, almost like a matter if national security.

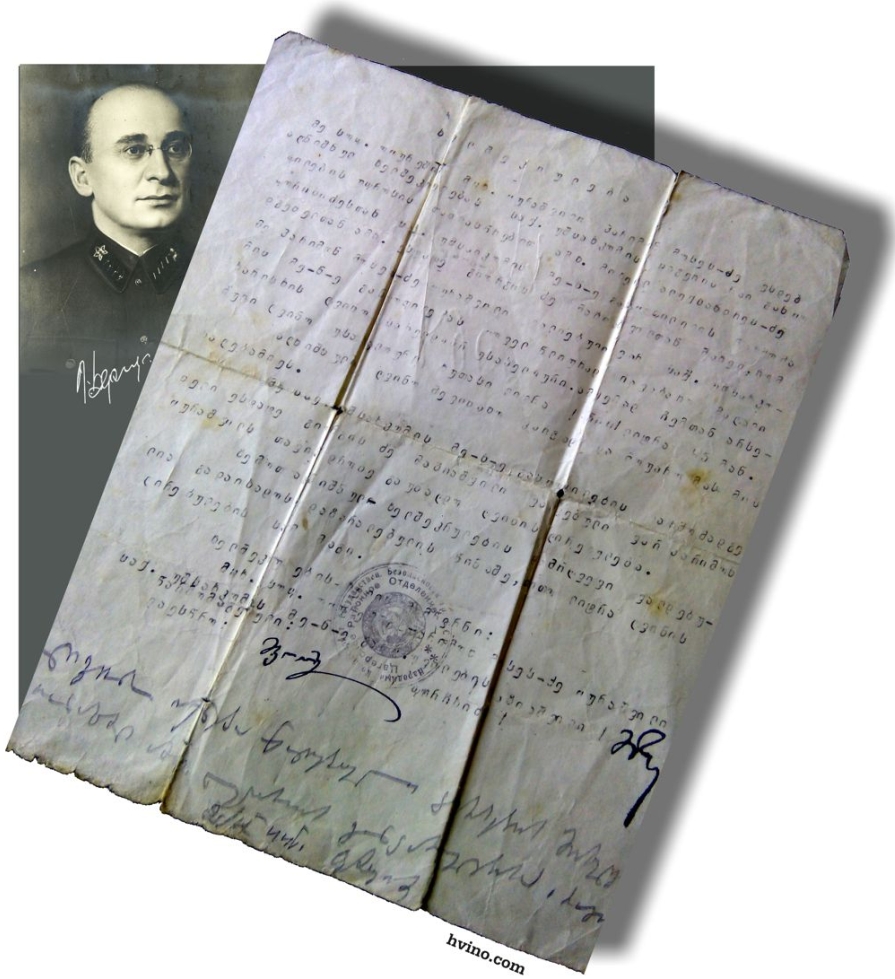

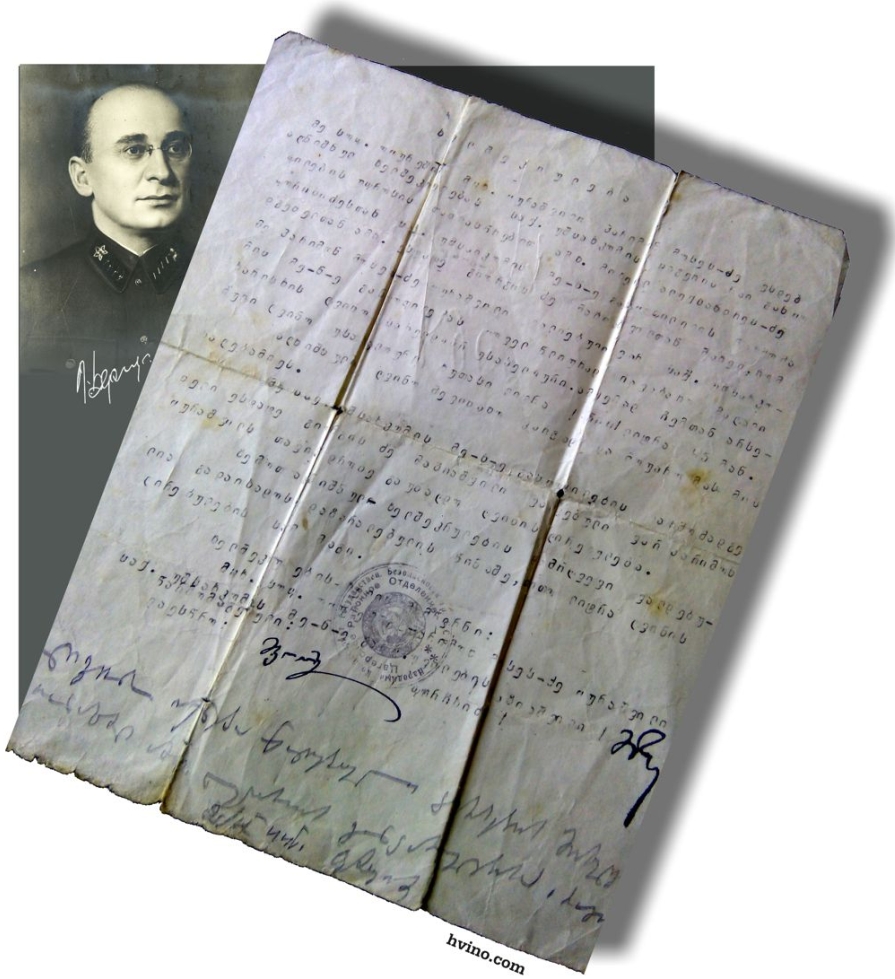

A unique evidence of this has been for decades kept in the house of Dato Chakvetadze, whose family has been making Usakhelouri for generations. Dato, who is one of very few today’s producers of this wine, handed me the original document dating from 1944. It’s a contract between the winemaker (Dato’s great grandfather) and several officers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. No, this is not taken from a novel by George Orwell or, God forbid, my namesake Franz Kafka, though the situation is absurd enough for either writer. The contract regulates the supply of “high-quality wine of Usakhelouri variety” produced by the winemaker, which all should be “preserved and shipped to the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs… in accordance with the order by comrade L. Beria”. Lavrentiy Beria (1899 –1953) was the closest aide to Joseph Stalin: he was the notorious chief of NKVD – the Soviet security and secret police. The officers of secret police actually counted the amount of Usakhelouri produced by every peasant, and made sure they did not retain any precious product for personal use or for selling in the market. It was unthinkable to disobey the order of Beria – the person who administered all the mass arrests, killings, and prisoner camps of the Stalin epoch. So it’s small wonder that almost nobody knew about this rare wine, and even fewer had ever tasted it.

Dynamite in a heavenly garden

Neither have I tasted Usakhelouri before, though I’ve taken part in quite some Georgian and international wine events, in my capacity of the publisher of wine information resource and catalogue, Hvino.com. So I gladly accepted Dato’s invitation to visit the enigmatic Usakhelouri homeland to taste this wine right where it is grown.

Neither have I tasted Usakhelouri before, though I’ve taken part in quite some Georgian and international wine events, in my capacity of the publisher of wine information resource and catalogue, Hvino.com. So I gladly accepted Dato’s invitation to visit the enigmatic Usakhelouri homeland to taste this wine right where it is grown.

Usakhelouri is rare not only because the production has been guarded by secret police. The productivity of this grape variety is rather low, which made many winegrowers use other, higher-yield species. In addition to low yield, Usakhelouri is very demanding to terroir. It can produce the right grapes only in very specific area – in certain geographical location, at certain altitude, on very specific soil, and with just the right amount of sunshine and rain. Planting all types of grapes is always a hard labour, but to produce Usakhelouri is a real challenge. The best Usakhelouri grows in the mountainous region of Lechkhumi in the Western part of Georgia. It may also grow in other regions, including Georgia’s main winemaking region of Kakheti in the East, but for the best wine only the grapes from Lechkhumi are used – actually only the ones grown in a small zone in Tsageri district, near villages of Zubi and Okureshi ▼Map .

In the Soviet time, in Okureshi a wine plant was constructed which produced the wine for the government’s needs. The old wine plant is now completely disassembled – not even a trace remains. No industrial building is spoiling the breathtaking beauty of this place, which is sometimes called “Georgian Switzerland”. The valley of river Tskhenis-Tskhali (meaning Horse River in Georgian) is surrounded by high and steep mountains, covered by fresh greenery in summer and by snow in winter. No wonder the agricultural land here is scarce. The only way to plant Usakhelouri is on steep mountain terraces, but they need to be cleaned from huge stones. Those sugar-white rocks look picturesque against the dark green slopes, but it is curse for the peasants.

The group of Usakhelouri enthusiasts (including Dato Chakvetadze, Teimuraz Minashvili, Dato Turabelidze and others) managed to clean the area to restore the production of top-level wine. They show me the neat new terraces of their vineyard, telling with a smile how they had to blast the larger rocks with dynamite, before the machinery could be used to clean his plots. I can only imagine the amount of effort and resources which Dato – a modest engineer in the past – had to invest into his vineyard project.

“We are preparing a revolution”

But the construction period is over, and Dato has been already selling his wine through several wine boutiques. He carefully controls every stage of winemaking process with equal attention – including the label design. So the wine is produced, bottled, and it sells well – what else is needed? But the winemaker is far from being satisfied.

But the construction period is over, and Dato has been already selling his wine through several wine boutiques. He carefully controls every stage of winemaking process with equal attention – including the label design. So the wine is produced, bottled, and it sells well – what else is needed? But the winemaker is far from being satisfied.

“What’s the next step?” – I asked Dato, and was surprised to hear that it was all just a beginning. “The next steps are plenty. Actually, we are preparing a revolution”.

The Usakhelauri enthusiasts have very ambitious plans. First and foremost, they want a plant of their own, which would focus on production of Usakhelouri only. Currently, all the winemakers, including Dato, have to rent out equipment and hire staff at large wine enterprises, to produce and bottle their Usakhelouri. “The results are good enough”, explains Dato, “but we could reach even better quality if we could control every moment of the process. I always tell them that mixing should be done by hand only, and no mechanical pumps must be used. But who knows what happens after I turn my eyes away? This kind of things can be ensured only at my own enterprise”.

Another urgent task is related to the government’s regulations. Believe or not, but currently Usakhelouri is not officially listed among Georgia’s wine appellations of origin. The Usakhelouri name is protected, but not in the same way as Kindzmarauli, Khvanchkara, or other famous and top-selling Georgian wines. The Usakhelouri enthusiasts are working with the wine regulating authorities to warrant the same status for Usakhelouri. Giorgi Samanishvili, director of National Wine Agency of Georgia, told me that his agency is planning to meet with the group of Usakhelouri producers in the nearest future. “The Lechkhumian Usakhelouri can be given the PGI [protected geographical indication] status. Local winegrowers should prepare a specification, and our agency will help them,"- said the head of Georgia’s regulating body responsible for winemaking.

Traditionally, Usakhelouri is known as semi-sweet wine (it contains up to 10.5 - 12.0% alcohol, 3 - 5% sugar and has 5 - 7 % titrated acidity). But Dato has plans to be the first to produce semi-dry and even dry versions of Usakhelouri. He told me that experiments have already brought excellent results. That would be quite revolutionary. I hope to taste this sometime.

The most ambitious task is to enter the global market, establishing Usakhelouri as a recognizable luxury brand. Towards this end, it may be helpful to develop wine tourism in that mountain valley and attract more wine lovers from abroad. The enthusiasts from Lechkumi have such plans. As long as the Usakhelouri team gets the needed investment and professional marketing support, going international seems like a realistic goal. It is a long way to go, but the product quality justifies all the effort.

I won’t be too much surprised if in a few years’ time this Georgian wine will find its way from the Kremlin dinners to the White House receptions or United Nations meetings at Palais des Nations in Geneva. But while high life events are important for prestige, I still hope Usakhelouri makers will not forget about the ordinary customers, and this rare wine supply will suffice to cater the needs of wine connoisseurs throughout the world.

Alexander KAFFKA, Ph.D., is publisher of Hvino.com, Georgian wine news portal and catalogue. He contributed this article to ICCommerce #5, 2015, available in English and Georgian languages. ICCommerce is journal published by International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). Hvino.com is member of ICC Georgia.

Source

(Here is the Russian version / НА РУССКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ)

by Alexander Kaffka

The officers of Stalin’s secret police actually counted the amount of Usakhelouri wine produced, and made sure the peasants did not retain a drop of precious product for personal use. It’s small wonder that almost nobody knew about this rare wine, and even fewer had ever tasted it.

Above all the fuss

29.10.2015. While visiting a supermarket in Tbilisi, a business traveler or a tourist can rarely miss the wine department. Usually, it is the liveliest spot of every shopping center, with some action taking place all the time. Surrounded by other departments’ lonely and ordinary-looking shelves, the wine place is the one, which is inhabited - by promoters. They are usually charming girls in colorful national costumes, who welcome you and offer free wine tasting. Yes, they are promoting their products but they are acting in such a delicate and friendly way, that you feel they just want to make your life better. The lucky traveler is offered a pretty amazing choice of wines to try, which are generously poured into full-size glasses (not microscopic plastic thimbles used for promotions elsewhere in the world). Easily and without any pressure, after one or two sips, you realize you are in a country where wine indeed plays a very special role.

After several visits paid to such wine departments, a typical foreigner may become perfectly aware of various brands of Kindzmarauli, Rkatsiteli, Mtsvane and dozens of other hard-to-pronounce but delicious Georgian wines – without spending a dime. But there is one wine, which is never offered for free, and for a good reason. It’s the Usakhelouri (here is how to pronounce: Oosa-hello-oory), dark red semisweet wine made of one of the most rare of Georgia’s whopping 400 grape varieties. Usakhelouri wines are expensive, hard-to-find in Georgia and almost completely unavailable abroad. Because of its rarity and high price, this wine is little known even among Georgians themselves. Usually bottled in elegant, slender non-standard glassware, Usakhelauri stands in solemn solitude on a remote shelf of the wine department, far above all the fuss of daily promotions, fenced by its price tag from the casual shopper, waiting for the right connoisseur.

I find it rather pointless to describe the taste of wine in writing. If you are lucky to be reading this in Georgia, you may invest in a bottle of Usakhelouri and taste it yourself in a company of friends (Yes, the price is rather high for a Georgian wine but still is comparable to the cost of a good dinner in a restaurant, so it is not unaffordable.) If you are outside of the country, but still are familiar of Georgian wines, just remember the best Khvanchkara you have tried - not too sweet one – and imagine something much more fresh, rich and elegant. If you like this idea, maybe you’ve just got another serious reason for paying a visit to Georgia.

The wine as a matter of national security

Why is Usakhelouri so little known? There are several reasons for that. Historically, most of the Georgian wine brands were primarily consumed by the vast markets of former USSR; the wines were mass-produced and well known to the people. Therefore, the Georgian wine names such as Saperavi or Mukuzani are still recognizable across the former Soviet republics; the sales in those countries do not require additional marketing efforts, and this is why these countries are still the largest importers of Georgian brands. In contrast, the Usakhelouri’s story is different. This wine was never sold to ordinary people. All the wine produced was shipped to Kremlin, to serve the drinking needs of the government and communist party leadership.

Why is Usakhelouri so little known? There are several reasons for that. Historically, most of the Georgian wine brands were primarily consumed by the vast markets of former USSR; the wines were mass-produced and well known to the people. Therefore, the Georgian wine names such as Saperavi or Mukuzani are still recognizable across the former Soviet republics; the sales in those countries do not require additional marketing efforts, and this is why these countries are still the largest importers of Georgian brands. In contrast, the Usakhelouri’s story is different. This wine was never sold to ordinary people. All the wine produced was shipped to Kremlin, to serve the drinking needs of the government and communist party leadership.When I say “all” I mean that literally 100 percent of the wine produced: Since 1930-40-s, the production of Usakhelouri was strictly guarded by the internal affairs ministry (NKVD), so not a drop of precious drink could be left without government control. Supply of Usakhelouri was indeed considered very seriously, almost like a matter if national security.

A unique evidence of this has been for decades kept in the house of Dato Chakvetadze, whose family has been making Usakhelouri for generations. Dato, who is one of very few today’s producers of this wine, handed me the original document dating from 1944. It’s a contract between the winemaker (Dato’s great grandfather) and several officers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. No, this is not taken from a novel by George Orwell or, God forbid, my namesake Franz Kafka, though the situation is absurd enough for either writer. The contract regulates the supply of “high-quality wine of Usakhelouri variety” produced by the winemaker, which all should be “preserved and shipped to the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs… in accordance with the order by comrade L. Beria”. Lavrentiy Beria (1899 –1953) was the closest aide to Joseph Stalin: he was the notorious chief of NKVD – the Soviet security and secret police. The officers of secret police actually counted the amount of Usakhelouri produced by every peasant, and made sure they did not retain any precious product for personal use or for selling in the market. It was unthinkable to disobey the order of Beria – the person who administered all the mass arrests, killings, and prisoner camps of the Stalin epoch. So it’s small wonder that almost nobody knew about this rare wine, and even fewer had ever tasted it.

Dynamite in a heavenly garden

Neither have I tasted Usakhelouri before, though I’ve taken part in quite some Georgian and international wine events, in my capacity of the publisher of wine information resource and catalogue, Hvino.com. So I gladly accepted Dato’s invitation to visit the enigmatic Usakhelouri homeland to taste this wine right where it is grown.

Neither have I tasted Usakhelouri before, though I’ve taken part in quite some Georgian and international wine events, in my capacity of the publisher of wine information resource and catalogue, Hvino.com. So I gladly accepted Dato’s invitation to visit the enigmatic Usakhelouri homeland to taste this wine right where it is grown.Usakhelouri is rare not only because the production has been guarded by secret police. The productivity of this grape variety is rather low, which made many winegrowers use other, higher-yield species. In addition to low yield, Usakhelouri is very demanding to terroir. It can produce the right grapes only in very specific area – in certain geographical location, at certain altitude, on very specific soil, and with just the right amount of sunshine and rain. Planting all types of grapes is always a hard labour, but to produce Usakhelouri is a real challenge. The best Usakhelouri grows in the mountainous region of Lechkhumi in the Western part of Georgia. It may also grow in other regions, including Georgia’s main winemaking region of Kakheti in the East, but for the best wine only the grapes from Lechkhumi are used – actually only the ones grown in a small zone in Tsageri district, near villages of Zubi and Okureshi ▼Map .

In the Soviet time, in Okureshi a wine plant was constructed which produced the wine for the government’s needs. The old wine plant is now completely disassembled – not even a trace remains. No industrial building is spoiling the breathtaking beauty of this place, which is sometimes called “Georgian Switzerland”. The valley of river Tskhenis-Tskhali (meaning Horse River in Georgian) is surrounded by high and steep mountains, covered by fresh greenery in summer and by snow in winter. No wonder the agricultural land here is scarce. The only way to plant Usakhelouri is on steep mountain terraces, but they need to be cleaned from huge stones. Those sugar-white rocks look picturesque against the dark green slopes, but it is curse for the peasants.

The group of Usakhelouri enthusiasts (including Dato Chakvetadze, Teimuraz Minashvili, Dato Turabelidze and others) managed to clean the area to restore the production of top-level wine. They show me the neat new terraces of their vineyard, telling with a smile how they had to blast the larger rocks with dynamite, before the machinery could be used to clean his plots. I can only imagine the amount of effort and resources which Dato – a modest engineer in the past – had to invest into his vineyard project.

“We are preparing a revolution”

But the construction period is over, and Dato has been already selling his wine through several wine boutiques. He carefully controls every stage of winemaking process with equal attention – including the label design. So the wine is produced, bottled, and it sells well – what else is needed? But the winemaker is far from being satisfied.

But the construction period is over, and Dato has been already selling his wine through several wine boutiques. He carefully controls every stage of winemaking process with equal attention – including the label design. So the wine is produced, bottled, and it sells well – what else is needed? But the winemaker is far from being satisfied. “What’s the next step?” – I asked Dato, and was surprised to hear that it was all just a beginning. “The next steps are plenty. Actually, we are preparing a revolution”.

The Usakhelauri enthusiasts have very ambitious plans. First and foremost, they want a plant of their own, which would focus on production of Usakhelouri only. Currently, all the winemakers, including Dato, have to rent out equipment and hire staff at large wine enterprises, to produce and bottle their Usakhelouri. “The results are good enough”, explains Dato, “but we could reach even better quality if we could control every moment of the process. I always tell them that mixing should be done by hand only, and no mechanical pumps must be used. But who knows what happens after I turn my eyes away? This kind of things can be ensured only at my own enterprise”.

Another urgent task is related to the government’s regulations. Believe or not, but currently Usakhelouri is not officially listed among Georgia’s wine appellations of origin. The Usakhelouri name is protected, but not in the same way as Kindzmarauli, Khvanchkara, or other famous and top-selling Georgian wines. The Usakhelouri enthusiasts are working with the wine regulating authorities to warrant the same status for Usakhelouri. Giorgi Samanishvili, director of National Wine Agency of Georgia, told me that his agency is planning to meet with the group of Usakhelouri producers in the nearest future. “The Lechkhumian Usakhelouri can be given the PGI [protected geographical indication] status. Local winegrowers should prepare a specification, and our agency will help them,"- said the head of Georgia’s regulating body responsible for winemaking.

Traditionally, Usakhelouri is known as semi-sweet wine (it contains up to 10.5 - 12.0% alcohol, 3 - 5% sugar and has 5 - 7 % titrated acidity). But Dato has plans to be the first to produce semi-dry and even dry versions of Usakhelouri. He told me that experiments have already brought excellent results. That would be quite revolutionary. I hope to taste this sometime.

The most ambitious task is to enter the global market, establishing Usakhelouri as a recognizable luxury brand. Towards this end, it may be helpful to develop wine tourism in that mountain valley and attract more wine lovers from abroad. The enthusiasts from Lechkumi have such plans. As long as the Usakhelouri team gets the needed investment and professional marketing support, going international seems like a realistic goal. It is a long way to go, but the product quality justifies all the effort.

I won’t be too much surprised if in a few years’ time this Georgian wine will find its way from the Kremlin dinners to the White House receptions or United Nations meetings at Palais des Nations in Geneva. But while high life events are important for prestige, I still hope Usakhelouri makers will not forget about the ordinary customers, and this rare wine supply will suffice to cater the needs of wine connoisseurs throughout the world.

Alexander KAFFKA, Ph.D., is publisher of Hvino.com, Georgian wine news portal and catalogue. He contributed this article to ICCommerce #5, 2015, available in English and Georgian languages. ICCommerce is journal published by International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). Hvino.com is member of ICC Georgia.

Source

No comments:

Post a Comment